“The Toyota Way” by Jeffrey Liker (personal notes)

Those are my personal notes on Jeffrey Liker’s book “The Toyota Way” (insert Amazon affiliate link here). Don’t drink and drive.

Continuous improvement

- A lean organisation is a learning organisation.

- The Toyota Way worships at the altar of continuous improvement — taking precedence over everything else, including uptime. It is the guiding principle, and a paradigm shift at that. Work clean, and then work fast.

- Continuous improvement refers to two things: reducing deviation from the standard, and improving the general efficiency of a system (by bursts — “kaizen”).

- As you reduce deviation from standard, you can focus more and more on improving the general effectivity of the system and work towards KPI targets, “make leaps”.

- The Toyota Way includes both radical transformation and incremental improvements: “Some large leaps, and many small steps”; big CI and small CI.

- Re-imagine the future state (for radical transformation): rather than starting with improving current processes, you might want to start with developing a future ideal vision for the whole process (customer-centric; design thinking), relieving you from any biases associated with the way things are currently set up.

- “Always develop a future state to strive for. Don’t stop at mapping the current state and chasing waste.”

- Re-imagine the future state (for radical transformation): rather than starting with improving current processes, you might want to start with developing a future ideal vision for the whole process (customer-centric; design thinking), relieving you from any biases associated with the way things are currently set up.

- Judge how well an organisation or organism is doing, not by how they are doing at a fixed point in time, but how much they have been improving in the recent past. Assess not based on a snapshot, but over a period of time.

Standardization

- Standardized processes are the sine qua non of continuous improvement.

- Without consistency in the current processes, there is nothing to improve on, to build upon.

- Current processes must represent the current best method of doing something.

- Standardized processes should be improved on, ideally by the floor workers — the people doing the actual work and most familiar with it.

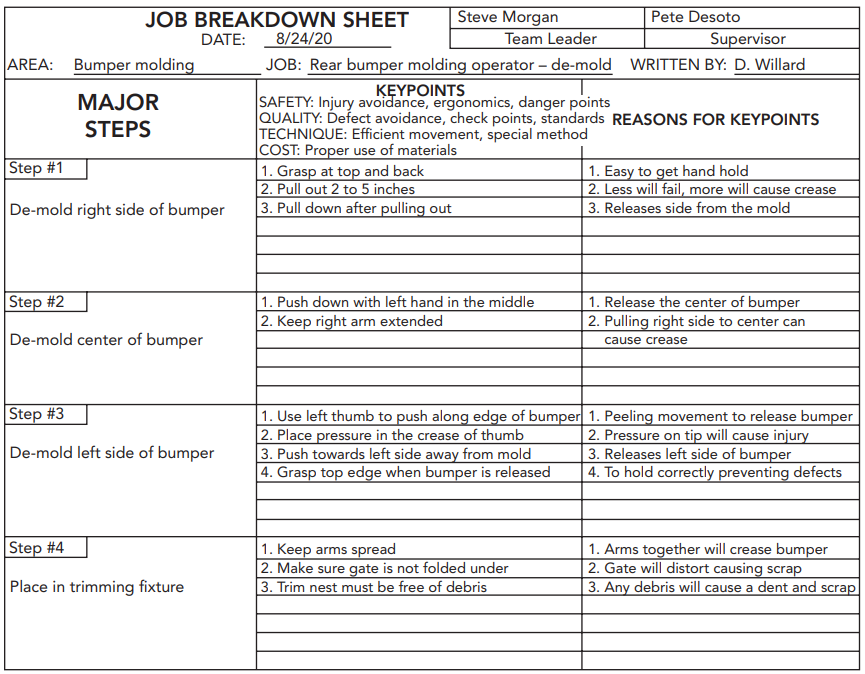

- Document the standard way of carrying out each process in detail, explaining the reason for each step.

- Spend extensive time alongside your trainees when they are starting and provide them with instant feedback on deviations from the standard. Gradually spend less time at their side.

- Training happens through repeated (deliberate) practice (“learning by doing”) and through corrective feedback (side-coaching).

- After training, this standard reference should be internalized and barely ever referred to.

- It should still remain visible (typically displayed “outward” at the entrance of the work station), as a useful resource to be able to check against, occasionally by the worker and more often by management during periodic checks.

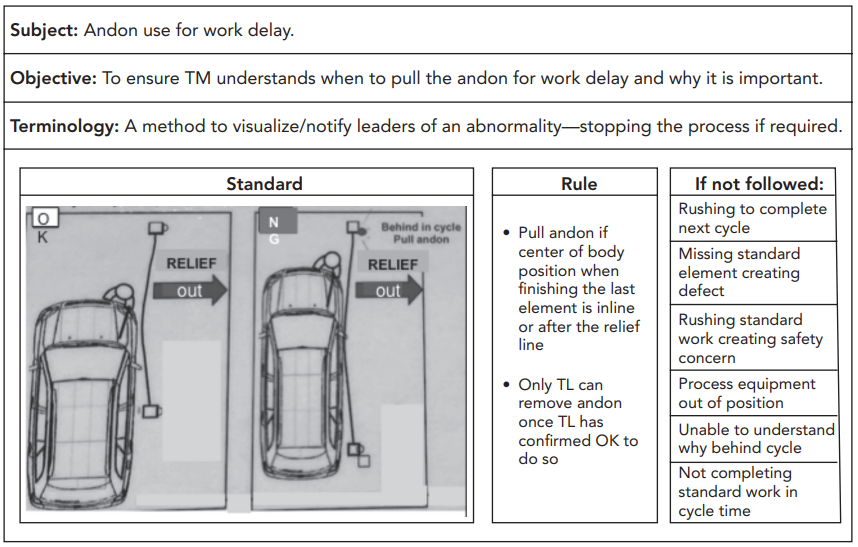

- Document rules and their objective as well as the reasons they were created in the first place (the hazards incurred if they are not followed)

- Display these documents prominently in space.

- Use clear, concise wording.

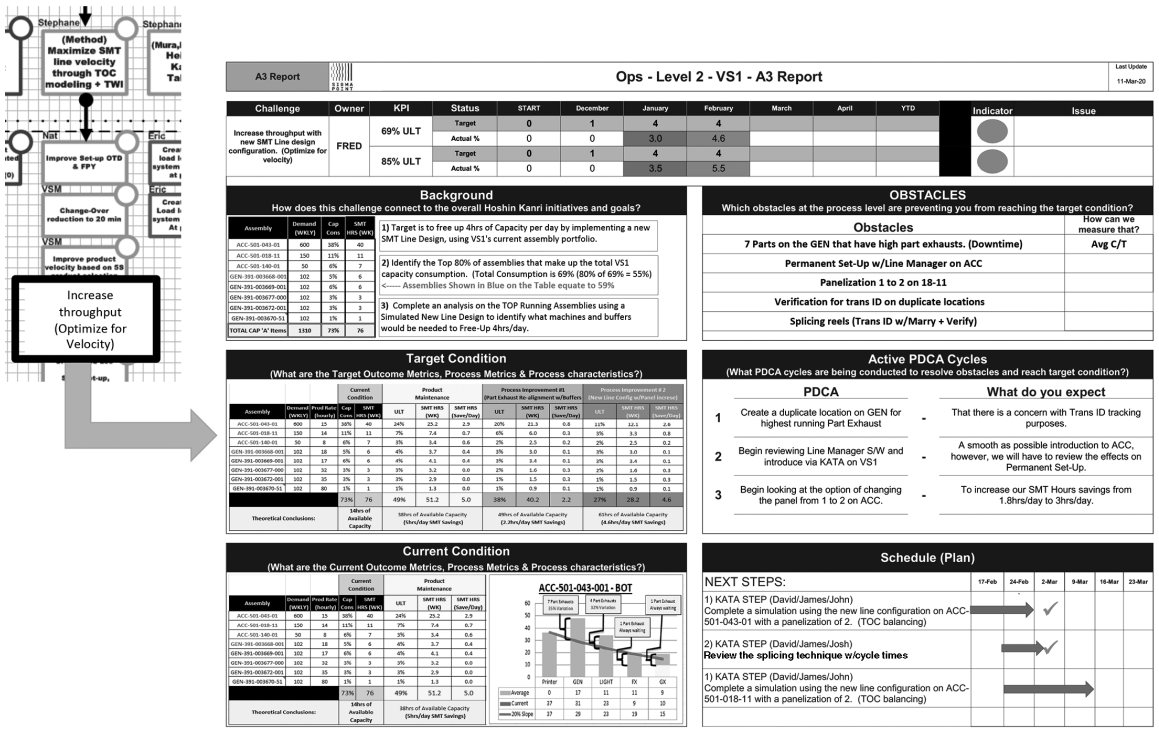

- Write A3s to present project (proposals) clearly, including timeline and numbers.

- “Enabling vs disabling (red-tape) bureaucracy”: enabling bureaucracy most often comes from the workers themselves, designing the standards (for themselves).

- By standardizing work (and knowing the time that each standard process takes), you can predict how much time an operation will take and can communicate this to the customer and plan around it.

- Inventory organisation: visually standardize the quantities and locations.

- Make lack of supplies or surplus of supplies visually easy to identify.

- Make it visually clear where something belongs (shadow board), when something is missing or when something is out of place.

- Routines are for organisations the equivalent of habits for individuals.

Continuous flow

- Continuous/one-piece flow is opposed to traditional batch processing.

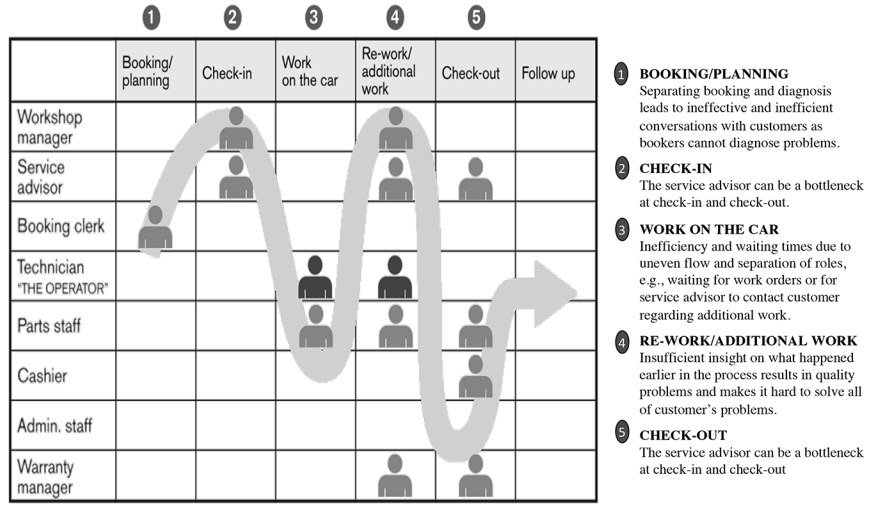

- Instead of having different departments processing items in batches for every stage of production, the idea is to have self-contained production lines with each one of these departments, and processing items sequentially, ideally one at a time, almost as they come, rather than in batches — and keeping minimal to no stock or buffer. Each line has all the work cells necessary to assemble a product. “From process islands to flow lines.”

- Just-in-time (JIT): deliver the right items in the right amount at the right time to the next work cell, or customer; and receive your items the same way from the previous work cell, or supplier.

- “Pull”, ask for items when you’re about to need them, rather than have them be “pushed” onto you.

- Having work items be “pushed” onto you takes no notice of your capacity or current state and is a recipe for disjointed work lines, inventory overstock and the associated wastes.

- Align your production time with the customer takt (with some buffer, “cycle takt”) : how often a customer buys a product (i.e. how fast you have to create, the time frame in which you must produce an item).

- You can use takt time (based on how many items need to be produced that day and the operational hours) to determine, based on a line’s or employee’s cycle time, how many lines or employees you need that day.

- In traditional batch processing, any one product the customer buys takes as much time to be produced as the whole batch it is part of — which is a lot longer than the time it would take in a continuous-flow set-up.

- Continuous flow increases safety, as smaller batches of material need to be moved around.

- Continuous flow is a double-edged sword. In traditional batch processing (where each cell can work off their inventory if the upstream process halts for a while), the final inefficiency is the inefficiency of the last process in the line. In one-piece flow (where each cell’s inefficiency affects the next cell), inefficiencies accumulate.

- This provides motivation for remedying the inefficiency of each cell and makes such improvements necessary, urgent and critical. In a way, this is full-on “fight mode”, aggressive to the point of inviting (surfacing) problems, in order to tackle them.

- Continuous flow makes problems immediately visible, “but is only useful if people are motivated and trained to solve problems.” — the Toyota Way is a technical and social system working together.

- Because of this insistence on tackling every problem immediately as they emerge, the learning curve and improvement rate of lean organisations is off the charts.

- Being confronted with and having to solve the problem immediately forces people to think, and in doing so trains them to become better thinkers, and, through increased engagement (considering the urgency of the problem) and responsibility (considering the problem endangers the company), better workers.

- In traditional batch processing, by hiding (upstream) inefficiencies, we postpone solving problems and potentially make the whole system a time bomb. Comfort leads to complacency (ignorance). In continuous flow, you have to fix problems right now, as they occur. There is no possible accumulation of problems.

- This provides motivation for remedying the inefficiency of each cell and makes such improvements necessary, urgent and critical. In a way, this is full-on “fight mode”, aggressive to the point of inviting (surfacing) problems, in order to tackle them.

- Continuous flow (and small inventory) lets you adapt to customer demand almost instantaneously.

- Instead of having different departments processing items in batches for every stage of production, the idea is to have self-contained production lines with each one of these departments, and processing items sequentially, ideally one at a time, almost as they come, rather than in batches — and keeping minimal to no stock or buffer. Each line has all the work cells necessary to assemble a product. “From process islands to flow lines.”

Levelling

- Decide on a weekly production target rather than a daily production target. This gives you room to use knowledge of external circumstances to adjust the production each day and level the overall work/stress. You can decide on working a bit less on certain days and a bit more on other days, and still meet the production target.

- Unevenness in production levels increases costs by making it necessary to have at hand the equipment, materials, and people for the highest level of production — even if the average requirements are far less. It is a waste.

- Levelling prevents overburdening and idling.

- Let there be small fluctuations in shift lengths, accounting for variations in customer demand.

- Use a small finished inventory to cover fluctuations in customer demand.

- Level the product mix in addition to the production volume. This also lets workers alternate between high-effort tasks/products and low-effort tasks/products, reducing overburden.

- Levelling the types of products being made prevents you from being wrong-footed if a customer unexpectedly orders large quantities of a certain item at the wrong time (e.g. long before this item gets produced in the weekly production cycle).

- By preparing way ahead for seasonal demands, you obviate the need for having the equipment, material and people (e.g. hiring of seasonal workers) needed to suddenly produce immense amounts of that seasonal product.

- Levelling prevents rendering certain workers expendable (e.g. those working exclusively on a production line failing to meet with customer demand). Levelling thus increases job safety, essential in creating a culture of respect for people and collective growth.

- Levelling takes precedence over respecting customer order — although this won’t make a big difference considering the levelling period.

- Level the work processes in the production line by trying to even out their cycle time.

- The production schedule is leveled and managed by the pacemaker, “pulling” (ordering) products from the assembly line.

- Make the schedule and current status (compared to the (levelled) schedule) easily visible.

Error detection (jidoka & andon)

- Set up error-detecting mechanisms and machines that automatically interrupt processes when detecting a problem or out-of-standard condition (“jidoka”; as in the Toyota loom). This ensures that no faulty item makes it to the next work station (let alone the final customer) and builds in quality.

- Detecting errors early and directly at their source makes it easier to understand the problems and to address them effectively, prevents the trail from getting cold.

- This controls and reduces quality risks associated with replacing humans with machines.

- Machines and automated processes should always be supervised by humans (for example in case of a detected error, or of a machine breakdown).

- When using automated systems, you should always know what they are doing under the hood, and be capable of performing their work should circumstances call for it. This fosters deep knowledge of the processes.

- Technology should support and assist people and processes; be subservient to them, and not the other way around.

- Be conservative in favouring machines over humans: “People are the most flexible resource you have. Automation is a fixed investment.”

- “People, not computers, can continually improve processes.”

- View (floor) workers not as replaceable machines but as intelligent agents, able to identify, understand and solve problems on the spot.

- People processes are easier to kaizen than machines.

- You can redeploy people to work on other tasks; you cannot do so with machines.

- “People, not computers, can continually improve processes.”

- Try and use simple, adaptable machines that you can repurpose.

- Error detection can take place at the human level or machine level in the work cell, or with additional tests (e.g. every couple stations (quality gate), or once the item has been produced).

- Let every station inspect the quality of the incoming product — do not just check quality once at the very end of the line.

- Let workers easily signal a deviation from standard or the beginning of a malfunction (defect in incoming item, in the item as you’re working on it, running behind, etc.) with a simple mechanism (“andon”) calling in a stand-by supervisor.

- This is a hallmark of Toyota’s commitment to quality control and continuous improvement.

- The idea is to troubleshoot immediately when an out-of-standard condition is identified, before things snowball.

- If no action is taken by a supervisor in the next minute, the whole line is automatically stopped.

- This bears witness to the radicality of quality control and continuous improvement at Toyota.

- Have the system and procedures already set up. Know what to do in the case of a quality emergency (just as you would in a safety emergency)

- Stopping the line is not penalized or seen negatively in Toyota (the opposite would); rather, it is the attention to quality that is celebrated.

- Make errors physically impossible or very unintuitive to make (error-proofing).

- Make errors visible, visually easy to identify. Let humans easily see that something is out of place or non-standard.

- A clean environment lets you detect problems or potential problems faster (× The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: see clearly, think clearly). By working clean, we make defects easier to notice.

- “The cleaning process often acts as a form of inspection that exposes abnormal and pre-failure conditions that could hurt quality or cause machine failure.”

- Cleaning is an integral part of the 5S: Sorting (out), organising, cleaning, standardizing (processes), sustaining (in the long run).

- Use redundancy to prevent errors (especially electronic+analog redundancy)

Waste

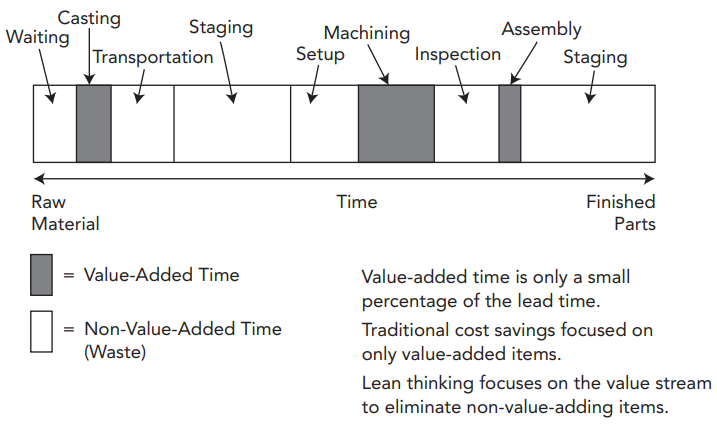

- Value should be flowing throughout the production process until delivery, without obstacles or halts (like a “free-flowing river”). The vast majority of lead time should be spent in value-added work contributing to the final product. Any interruption to this flow of value is waste and should be eliminated.

- The main wastes are: unnecessary transport (of goods or information), ineffective processing, defects, wasted time, overproduction and excess inventory.

- Unnecessary transport increases lead time.

- This also applies to transport of information and moving information in and out of storage, or between processes.

- Ineffective processing is wasteful and can be remedied with using better tools and having better resources available.

- Over-processing is equally wasteful: providing higher-quality products or services than is necessary is a waste (working fast vs working clean; “good enough”).

- Defects costs time due to detecting, correcting and discarding or recalling.

- Workers waiting, slacking (e.g. due to absence of immediate deadlines) or needing to move much in the space are a waste as this time doesn’t provide any value in the overall process.

- Continuous or maximal use of machines or labour can be wasteful. Continuous use of machines and labour can lead to overproduction (or overburden) and turn out to be a waste.

- Focus on the value stream instead of surface processes. Waste reduction should be directed at the value stream rather than surface processes. It’s fundamentally not about the wasted time of the machine or worker, but the wasted time of the product as it is being made (e.g. sitting somewhere instead of undergoing a value-adding change). Instead of producing as much as possible, focus on eliminating non-value-added processes and shortening the product’s lead time.

- Efforts to cut waste by working machines and workers as much as possible can be counterproductive and actually increase the overall waste (through overproduction, or overburden)

- It is better to periodically halt the machines and assign new tasks to your workers rather than overproduce.

- The faster process in the (one-piece flow) assembly line doesn’t have to be working all the time (creating inventory and overproduction) — though ideally this doesn’t happen by means of levelling processes or taking a process “off-line”.

- See material as (having costed) labour and let this be motivation to save material.

- Overproduction leads to overstaffing, unnecessary transportation and excess inventory.

- Excess inventory costs money and masks problems

- Keep minimal inventory.

- Excess inventory requires extra storage, costing you money and space; and ties up capital that could be invested elsewhere.

- Excess inventory means items are becoming stale, and greater quantities need to be discarded in case of an error in a batch.

- Having extra inventory hides away and lets you ignore defects (defective products can be thrown away as there are extra), equipment downtime, long set-up/changeover times and late deliveries from suppliers (as they then do not visibly impact the output directly in any critical manner)

- “The more inventory a company has, the less likely they will have what they need.”

- Should it come to that, you can use sales tactics to get rid of excess inventory.

- Unnecessary transport increases lead time.

- Identify and measure waste and bottlenecks across all processes. Having to call external contractors to repair or inspect machines because of lacking in-house expertise can be a major bottleneck for example.

- Unused employee creativity is wasteful as well; this ties in with the company culture.

- When there doesn’t seem to be any prominent waste anymore, resort to re-imagining the future state to not get stuck with the way things are currently set up.

Problem-solving

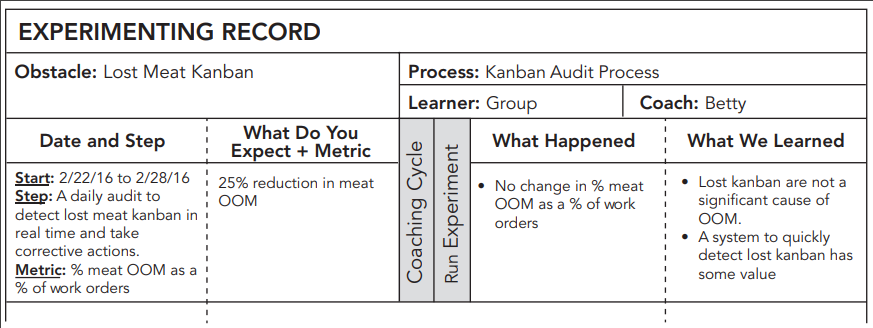

- The lean mindset is scientific thinking.

- Do not assume anything: conduct experiments (e.g. in a pilot) instead of directly implementing an assumed solution.

- Learn through experiments and trial-and-error; put practice first.

- Any hypothesis is tested with a practical experiment. Until results prove it, it’s just blind guessing. “Answers will be found by test rather than just deliberation.” “Learn by experimenting.” Learn by doing, and make many mistakes.

- Use facts and measurements as the basis for reasoning, experiments (e.g. measured performance gain) and for reaching conclusions. Gather data and facts to define the problem.

- Build in quality in the exchanges by going and confirming the facts for yourself: “you are responsible for the information you are reporting to others.”

- Identify the problem with highest priority and address it (fast).

- To do so, you can for example review the most common sources of incidents (andon pulls) in a Pareto chart.

- If the problem is not solved after a couple days of trying, escalate it to your superiors.

- Proposed changes should always be structured as experiments.

- The steps are as follows:

- Identify the problem and explain its importance and priority (compare the current state to the ideal state to clarify the problem)

- (For complex problems: break it down to a set of subproblems and decide on the highest-priority subproblem)

- Set a challenging target (based on current metrics)

- Analyse the root cause (go to the gemba (where the actual work takes place) and ask “why” 5x; analyse based on facts)

- Draft a countermeasure

- Implement it (together with the people affected by the change)

- Discuss the results, share what was learned (metrics are the sole indicator and proof of the value of your change)

- Standardize the new process if the results were fruitful

- (For complex problems: Tackle the next subproblem)

- An alternative model would be: identify, explain importance, hypothesis, methods, results, learnings, next step.

- These experiments, together with documenting past experiments, constitute the basis of a learning organisation.

- Workers and managers should experiment as frequently as possible.

- Foster a culture of experimentation and let your coworkers try out their ideas for improvements, methodically.

- Tackle one problem at a time.

- Apply root cause analysis to develop a deep understanding of the problem.

- Honda R&D & first principles: “The problem-solving steps were similar, except in place of “Find the root cause” was “Understand the physics”. For many of the physical hardware problems that engineers face in the automotive industry, there are opportunities to ask why in a deep technical sense.”

- Standing in the circle: standing in a circle drawn on the floor and observing your surroundings for a couple hours (“observing deeply”).

- By observing your surroundings, you notice how the work is being carried out and where there is room for improvement; this lets you gain insights and is helpful for problem solving and continuous improvement.

- When trying to solve a problem, go to the shop floor, see things for yourself, talk to the people.

- You might be asking “wrong” questions or puzzling over dilemmas because of wrong assumptions. These assumptions make your questions nonsensical. The solution to or cause of the problem might be a lot simpler than you expect — yet impossible to uncover by only “looking at your screen”.

- “5% of the time of NUMMI team leader is spent observing the team working in order to anticipate problems.”

- When trying to solve a problem, go to the shop floor, see things for yourself, talk to the people.

- By observing your surroundings, you notice how the work is being carried out and where there is room for improvement; this lets you gain insights and is helpful for problem solving and continuous improvement.

Management

- Prioritize (long-term) survival.

- Be self-reliant; independent from investors and their will; and developing in-house expertise if necessary (can be through hiring).

- “A strategy to deal with an uncertain future (external) should fit with the development of capabilities (internal)”

- Be self-reliant; independent from investors and their will; and developing in-house expertise if necessary (can be through hiring).

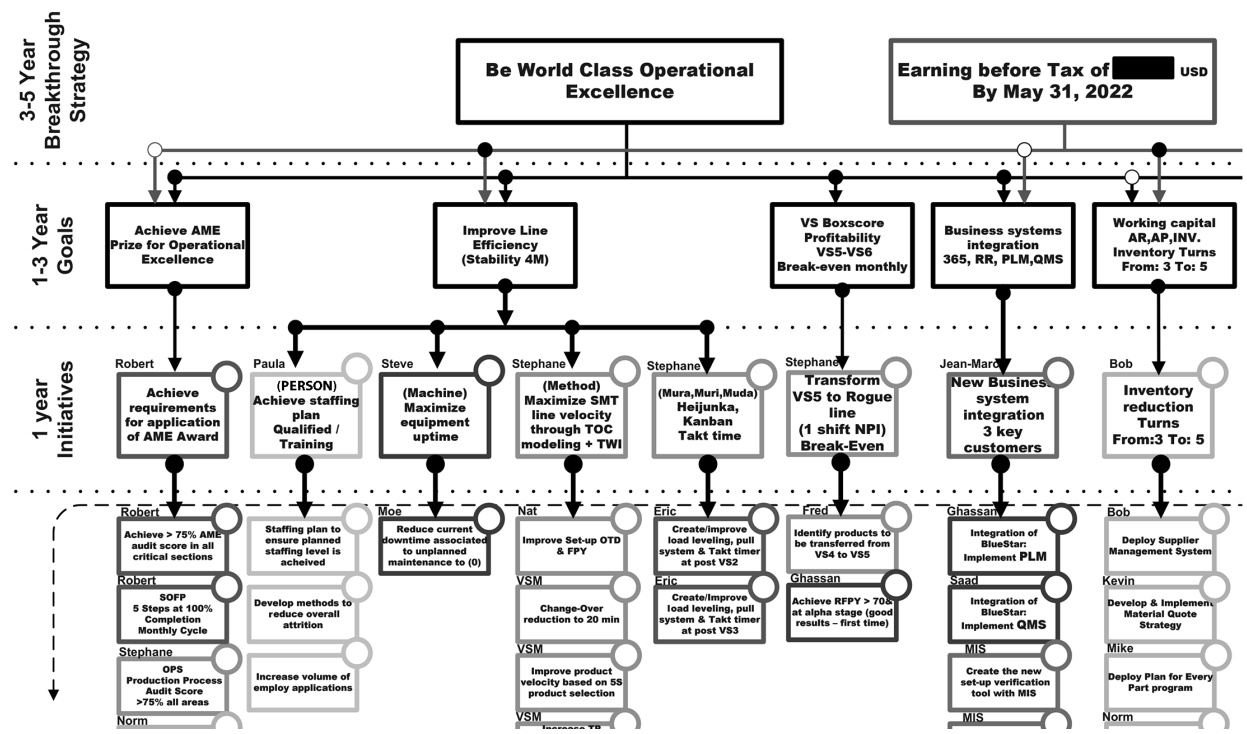

- Create a strategy.

- Have a global vision, a 3-5-year plan and a breakthrough 1-3 year plan.

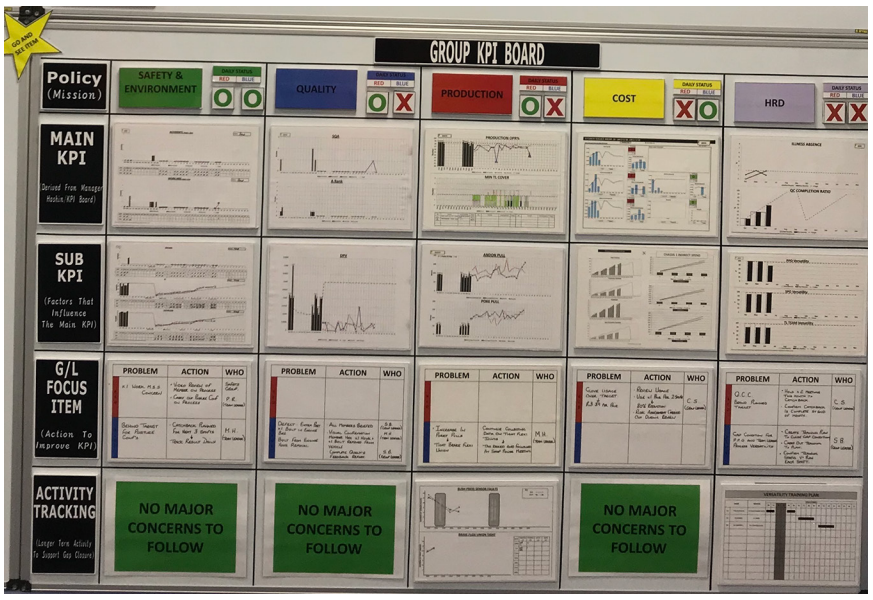

- To achieve the breakthrough 1-3 year plan, set 1-year goals based on the current condition with single-point accountability. Set monthly targets and compare the current condition against them on a visible dashboard.

- You only ever see the next step.

- Have a global vision, a 3-5-year plan and a breakthrough 1-3 year plan.

- Decide on clear KPIs (e.g. customer satisfaction, profits). Have KPIs for different areas (e.g. quality, cost, production, safety) and causal sub-KPIs (that you can take action towards). Occasionally track more specific problem metrics affecting main KPIs.

- The general objectives of any business should be quality, cost, delivery, safety and morale.

- Let your product development be consumer-centric. Study surveys of consumer tastes. Do first-hand market research by putting yourself in the client’s shoes. Meet your customers. Talk to them and listen to them. Do user tests, watching them use your product and letting them describe their thought process out loud. Use specs.

- See your organisation as a system, and be aware that short-term improvements might lead to long-term wastes, or vice versa. Beware of short-term results motivated by money. Let everything be an input and work towards your broader vision. Have an eye for deeper changes.

- Effective and sustainable organisations need both organic (adaptability, flexibility, self-renewal, resilience, learning, intelligence) and mechanistic attributes (standard processes); “combining the advantages of craft and mass production”.

- Organic attributes are the characteristics of living beings and systems, and what will ultimately ensure the organisation’s survival. Treat and view your organisation like a living system, not like a machine.

- The world isn’t mechanistic; it’s a system; thus your way of operating and dealing with it should be adaptive.

- Break down the system of the company into smaller autonomous systems in order to manage the whole. Let each one of your teams control their system at their level, such that the whole system can be controlled, like an organism. Explain your vision for the company and after everyone is onboard, divide and conquer.

- Organic attributes are the characteristics of living beings and systems, and what will ultimately ensure the organisation’s survival. Treat and view your organisation like a living system, not like a machine.

- Creating a culture (e.g. of continuous improvement) takes time and requires constancy in the management (who ideally “worked his way up” from the shop floor) and in the workers (job safety on the organisation’s side and commitment on the worker’s side — making oneself available to be grown)

- Using surface-level lean tools without a deeper-reaching change in culture will only provide short-term relief, and the system will eventually devolve (“mechanistic lean”).

- Hire coaches, not experts. Hire coaches (who develop the people and culture), not experts (who apply surface-level lean tools which will yield to entropy once they leave).

- When introducing change (e.g. lean), start with a pilot in a localized area, let it develop fully and only then let the pilot help deploy change in other areas, slowly, section by section, rather than directly across the board. Each deployment is a learning experience for the next deployment. Cultural change takes time. Having a “model line” lets other workers in the company understand lean and have an example, see it for themselves (cf. trips to Toyota plants in Japan).

- Deliberate culture: be intentional in the culture you want to create in the company; “the beliefs, values and basic assumptions that we want our people to hold dear and act upon”. For this to happen, first select, then develop people. Don’t only develop people, but also develop teams.

- Favour intelligence over knowledge. Hire people with the potential to learn the domain skills, with the ability to think and work in teams (cultural fit) the more important asset. “Toyota rarely hires veteran electricians, or mechanics, or welders, or painters. Instead, people are hired for their potential to learn these skills. […] The ability to work in teams, and most of all to learn to think critically and solve problems, is more important. Toyota believes it can develop these people to be exceptional.”

- “Hire people who are good raw material and then grow them through challenging experiences and coaching to guide them along the way.”

- “Individual success can happen only within a team. Strong teams require strong individuals.”

- “Every Toyota employee is expected not just excel in his current role, but to work toward higher levels of performance with enthusiasm.”

- “We accept challenges with a creative spirit and the courage to realize our own dreams without losing drive or energy.”

- Managers should be at the “gemba” often (the place where the actual work is done, e.g. manufacturing), and be familiar with it, even be able to replace workers if necessary. Management decisions shouldn’t take place in an ivory tower but very much in contact with the shop floor.

- Likewise, team supervisors should spend a large amount of their time doing the work that their team is doing.

- Talk to people, gather feedback, get their ideas and approval even before you formally propose the idea (nemawashi).

- Respect, trust, challenge and grow your people.

- Respect to people extends to customers, suppliers and business partners as well.

- Work very closely with your key suppliers, letting them take part in your design process. Challenge/develop your suppliers on quality, reliability, cost and processes.

- Job safety is essential in respecting your people. (× All About Love: only in a relationship of constancy can love grow, can one foster growth).

- “Team members” vs “variable workforce” (needing to decide after two years if they want to join the team or quit): the variable workforce provides the buffer for fluctuations in work demand, guaranteeing team members job safety.

- Don’t lay off; relocate. Move your employee to another work cell rather than lay them off: it will be one worker less to train, and their time with Toyota will contribute to the overall culture. (Internal turnover.)

- View (floor) workers not as replaceable machines but as intelligent agents, able to identify, understand and solve problems on the spot. “People are the most flexible resource you have.”

- Engagement, growth, learning and training happens by giving your people seemingly impossible challenges (which, it turns out, are actually possible), and giving them room to fail. Let your people decide on the method to achieve the challenge, give them agency.

- “Mr. Ohno could be very critical when he saw something wrong. It was very difficult for some people to take. And often we would work into the evening to solve problems. But then at the end of the day, even at 7pm at night, he would gather us all together and explain why he was critical that day. Everyone, even the junior workers, appreciated that he was trying to teach them. He was interested in developing everyone to their potential.”

- Leaders should be coaches (× Improvise!), teaching new ways of thinking; empowering people and removing obstacles; and being models in their behaviour.

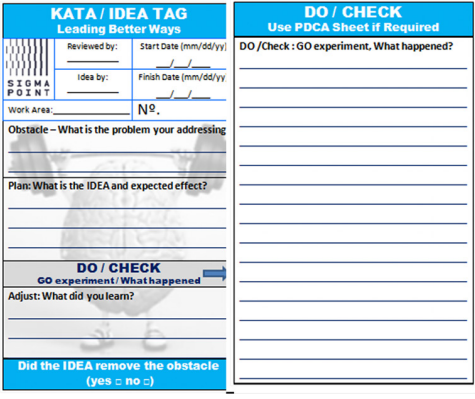

- “People change their habitual ways of thinking by deliberately practicing new ways, initially with some simple practice routines, aka kata.”

- The “Mindset ⇆ Behaviour” loop needs to be kick-started by an effortful, intentional initial jolt.

- When coaching, let the coachee do the thinking and figure things out for themselves, instead of giving them the solutions. Train and encourage workers to think, to think critically, to think for themselves.

- To provide effective feedback, give the feedback immediately after the behaviour, focus on the behaviour and not the person, and do this in a context of true compassion for the person you are coaching.

- Aim for a general culture of coaching and learning.

- Passing on knowledge is an act of love, and is to be met with respect and honour towards the teacher (sensei).

- “Clarify the skills and knowledge that you need to further develop yourself.”

- “People change their habitual ways of thinking by deliberately practicing new ways, initially with some simple practice routines, aka kata.”

- Focus on improving the system, not placing blame.

- Respect to people extends to customers, suppliers and business partners as well.

- Enforce a formatting of routine cross-managerial reports as bulleted lists, easy to read.

- Visual management tools: show all important information clearly on a dashboard, in a way that aids your thinking.

- Make delays, abnormalities and schedule easy to see. Include change point management: any changes that could impact the shift (e.g. new trainee, new tool being trialed) and the actions taken.

- Favour paper over digital dashboards.

- Screens tend to be used by only one person at a time; you want your dashboards to be seen and used by everyone.

- Support your employees and the team through visual management tools.

- More generally, use diagrams and other visual tools to facilitate understanding a situation, process, system and thinking about it (e.g. mapping factory workers’ walking path, or a customer’s user journey)

- “Use your feet to investigate processes and not your computer (go to the gemba); use your hands to draw the flow (use visual aids).”

- Aim for a ratio of 4 team members for 1 team leader, at all levels. (Just like Japanese schoolchildren identify with their small group of four to six students, “han” — cf. “fingers” in XR).

- Competition is to be valued, and competing organisations can learn from each other; they are a drive for relentless improvement. Foster competition to foster improvement, and for accelerating improvement and progress (generally as a species).

- Partner up with other businesses.

- Engineer using set-based design, rather than point-based design: come up with many possible options at first, then narrow them down based on different factors and perspectives (× Improvise! (brainstorming)). This prevents you from having to iterate very many times on a design prematurely decided on.

Lean in other domains

- Information JIT: deliver the right information at the right time in the right amount (e.g. to workers/volunteers: handbook vs. on-site briefing).

- Kanban-based pull systems can be applied to information flow.

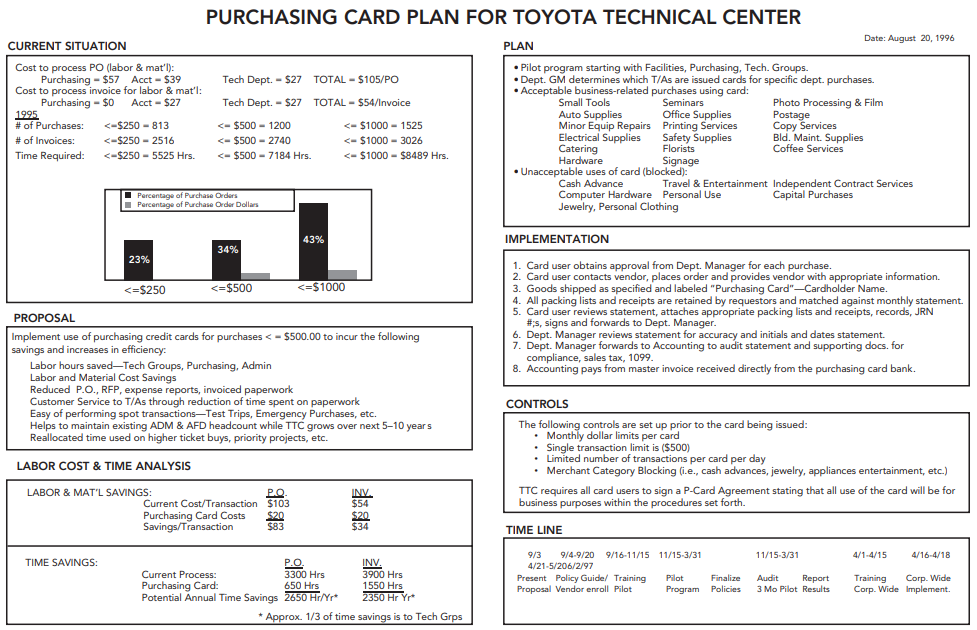

- The GM model lean office: “it created a formal kanban system for supplies, and as a result, the office rarely ran out of anything. There was a place for everything and everything in its place.”

- “Spend a little time each day learning something new.” (One-piece flow applied to life.)

Other

- “Everyone should tackle some great project at least once in their life.”

- “Can you get it done a year earlier?”

- “What is your next step (next experiment) ? What do you expect? How quickly can we go and see what we have learned from taking that step?”

- “Labour harmony”: when everything flows, and the workplace is like a symphony.

- When the culture is not there and management doesn’t make it feasible, either “find greener pastures”, or practice what you can.

- Clearly identify what doesn’t add value and eliminate it, throwing money at it if necessary. What is non-essential is wasted time.

- Give a (simple) name to developmental programs, practices, concepts. They then have an identity and become clearer.

- Stick with and improve on the system you’ve built.

- “If there is anything to learn from Toyota, it is the importance of developing a system and sticking with it and improving it.

- Jeffrey Liker met with very many people who each let him understand different things about the Toyota way, changed him in a way; it is wonderfully captured in the book’s acknowledgments and very inspiring to read each of these people’s contributions to enriching and completing the author’s understanding of the Toyota philosophy. “I learned from him…”